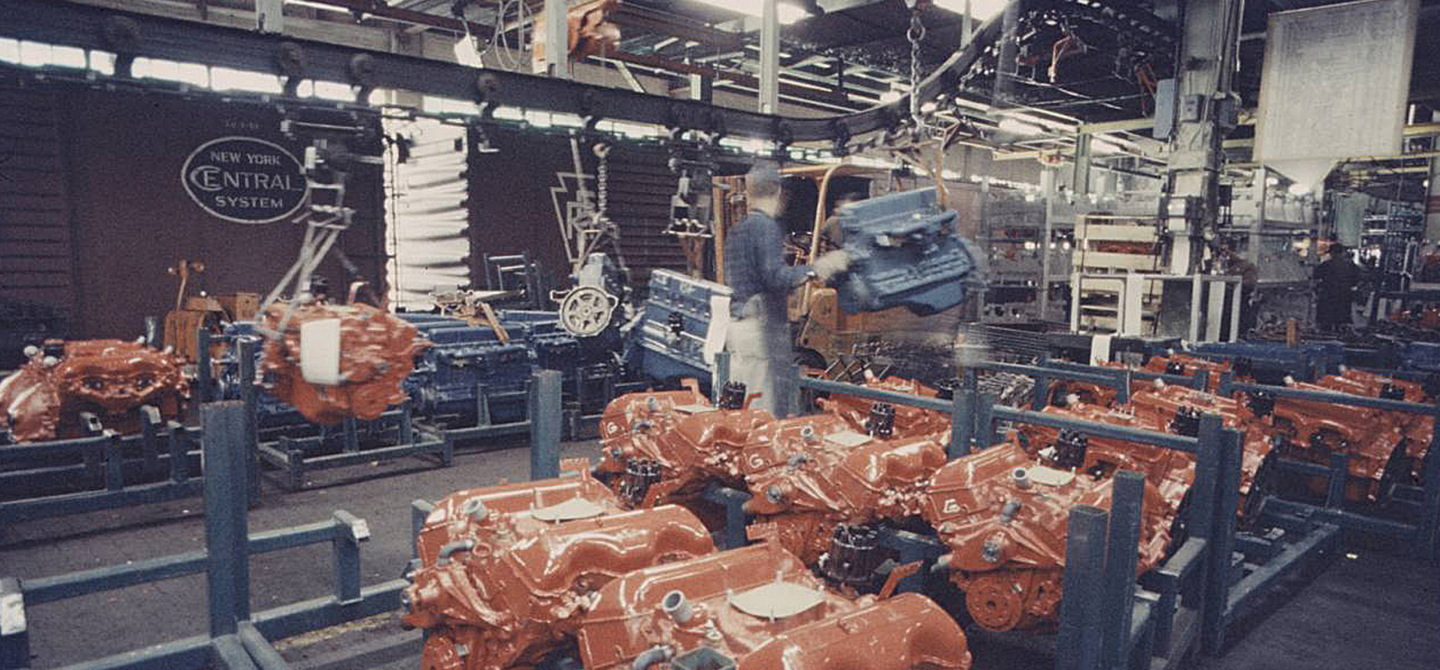

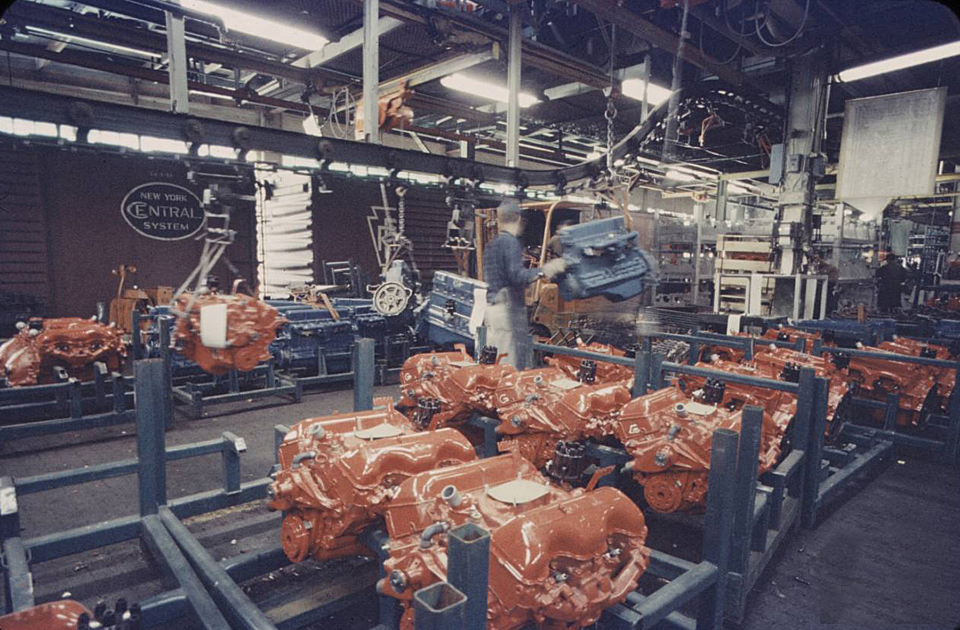

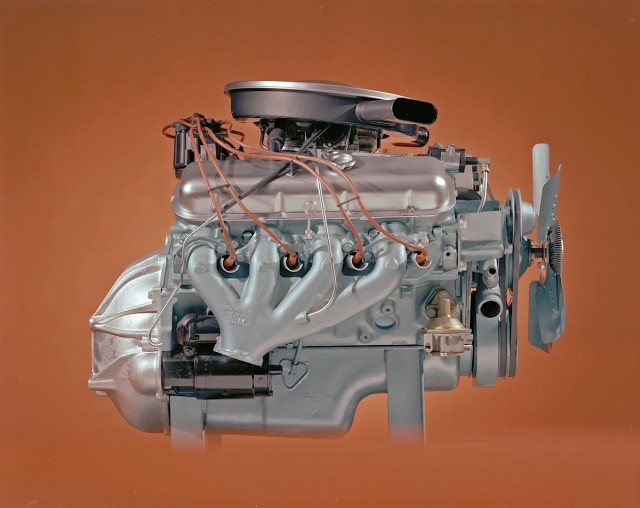

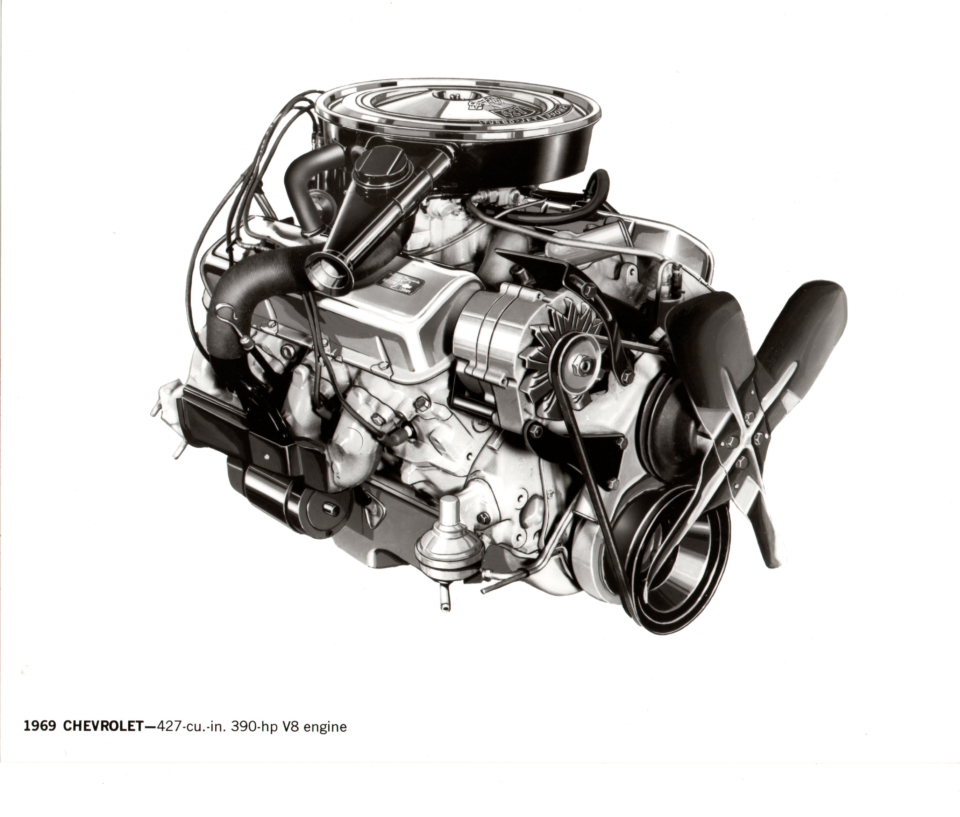

The year 1965, marked the first year the Chevrolet big-block, 396 cubic-inch engine, was released to the public. The elusive 1965 Chevelle Z-16 received this new big-block. This parts combination then spurred the 1966 Chevelle SS 396. These engines were also fitted into Corvettes, and later, into Novas, Camaros, and Impalas. They were refined, and saw a bump up of power, which reached a pinnacle in 1970. The big-block engine grew in size, and set the stage for the storied horsepower wars, and forever changed the history of Chevrolet.

All photos courtesy of General Motors 2014

Before the mighty LS6 became King of the Hill, you can trace the big-block’s ancestry to the Mark I 348/409 engine that adorned early ’60s Impalas. This big-block never gained the popularity of the later models, but that’s where it all started. Taking a step back in time, we caught up with Bill Howell, now of Howell EFI, who worked on some of the very first big-block Chevrolet engines.

While at General Motors, he worked on the first 409 big-blocks, as well as the Mark IV big-block. He started his journey in the summer of 1961, and worked on Chevrolet engine development until September 1987. From there, he started Howell EFI, which specializes in wiring up electronic fuel-injection. Even though he’s now a young 81 years old, he remembers 1961 like it was yesterday.

CHC: Tell us about your history with Chevrolet and the big-block engine.

Howell: “I went to work at Chevy in the summer of 1961. At that time, our NASCAR racing engine was the 409. Even though we were not actively participating in NASCAR, our engine group chose to try and keep abreast of what was going on, and, we had a little bit of backdoor help going out to people like Rex White. There might have been another team or two but pretty much it was a closed shop. The 409 was running a Carter AFB, the biggest carburetor that Carter made in a four barrel. It made about 425 horsepower on a dyno. All the numbers from that era were numbers that would be lower if you use today’s correction factors on them.”

CHC: Is there any information the public doesn’t really know about big-blocks?

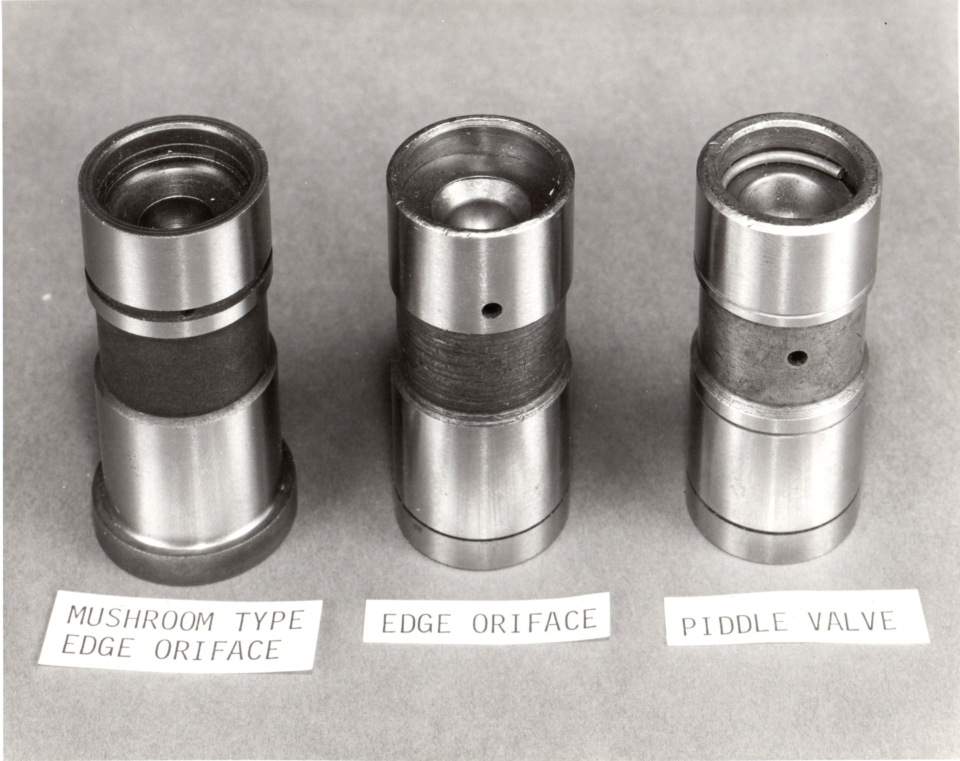

Howell: “I’ll tell you what, we struggled a little with the big block, especially in the performance Corvettes. It was tough getting the oil flow to where we could live with a wet sump, four-quart oil pan. At the time, we had a mechanical lifter with very high oil flow, because of its design. The problem with that, was, the lifter was designed by the Chief Engineer at that time, and he wouldn’t talk about changing the design. The lifter leaked oil inside the engine like crazy, and it created a lot of oil flow. If you can’t get the oil back to the oil pan quick enough, the engine eventually runs out of oil pressure. So, we struggled probably more than anything with that. Oil flow took quite a while to get under control.”

“Also during that time period, engineers went from five- to four-quart oil pan, which was a big problem. The reason for the four-quart pan was to get the engines positioned lower in the cars. In the Corvette, it had to be fairly close to the ground – closer than a passenger car. The trucks weren’t a problem, but if you put a big-block in a Camaro or something, it’s bound to end up with the oil pan closer to the ground.”

CHC: Why did the 409 go away?

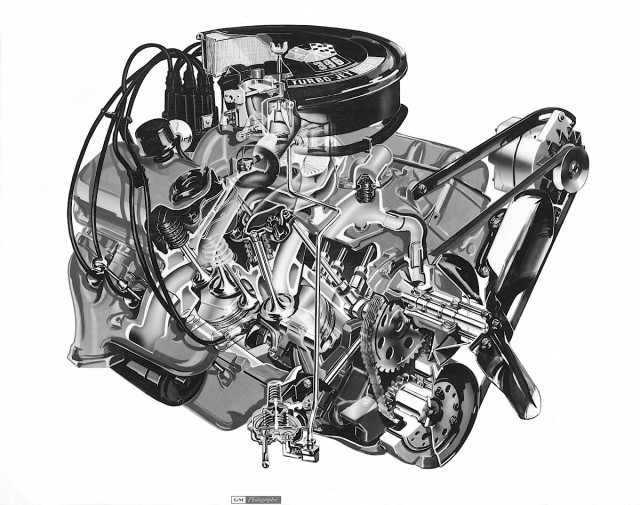

Howell: “The 409 was not a very successful NASCAR racing engine. It was originally designed as a truck engine. Even though the corporation had forbidden our participation in automobile racing at the time, Pontiac was doing it out the backdoor. I don’t think that there was any Buick or Oldsmobile performance going out. Chevrolet didn’t want to get left behind, and we had engineers and people in charge that felt performance was something we needed to keep abreast of. Around 1960 or ’61, they decided to design a new engine to incorporate everything that they thought they knew. They developed that engine in 1962, and it was called a Mark II.”

CHC: What’s the story of the Mark I, II, IV naming, and why wasn’t there a Mark III?

Howell: “The Mark I was the 409, the Mark II was the engine that we designed in ’61 or ’62, and there never was a Mark III. At the time, Studebaker/Packard went out of business. They had a big V8, and GM was contemplating buying the tooling from Packard and making a V8 for General Motors. That was going to be the Mark III. It never happened. In-house, we went from the Mark II to the Mark IV, so we stayed with the Mark IV. The Mark IV is the big-block we all know now.”

CHC: What are your thoughts on the big-block?

Howell: “It’s been an engine with a lot of potential over the years. Drag racers have done a lot of good with it, along with some boat racers. What impressed me, was at the time I retired in ’87, they still hadn’t developed great port flow. Now, that’s a different story.

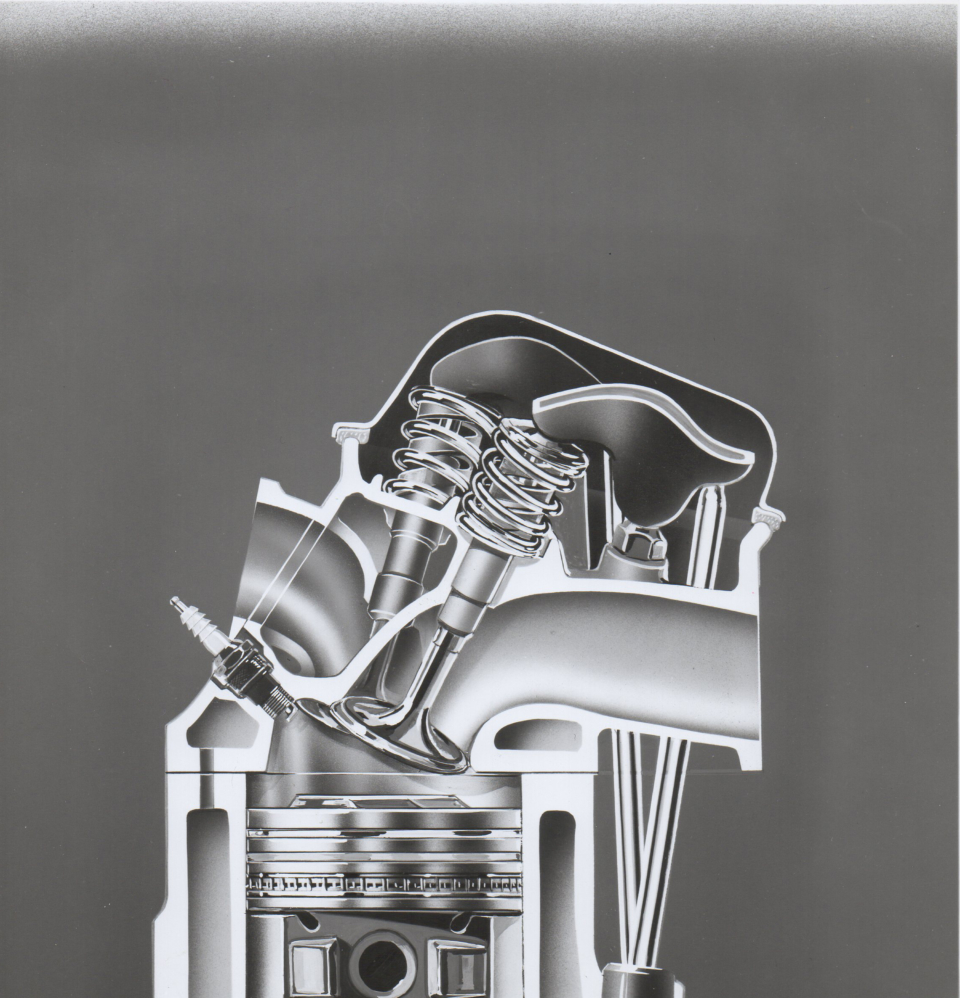

One of the things I was privileged to help with, were the first samples of the Optron. With this machine, you could actually watch the motion of a valve at high speed. As you could image, camshaft and valve-spring design was very difficult at high engine speeds, because the only tool you had was a strobe light. You could take a strobe light and see the valve springs surging and you could see the valve bounce, but you couldn’t really develop a better system. The Optron came along about 1963, maybe ’64.”

CHC: Can you explain what an Optron is?

Howell: “An Optron reflects light off of a polished edge – like on a valve spring cap. You don’t have to have a running engine, and you can cut away part of the head and actually watch the edge of valve. It transfers that motion onto an oscilloscope. With this, you can watch the electronic trace on an oscilloscope to see the valve profile. It should follow the camshaft profile up and down, but as soon as you get to higher speeds it quits following the camshaft perfectly and starts bouncing when it seats or lifts off the lobe when it goes over the nose of the camshaft. I ran the very first Optron that ever came to Chevrolet engineering back in the early 60’s, and the room had to be absolutely dark. The thing was set up on a surveyors tripod, and if you bumped it, you lost a half a day’s work trying to get it lined up again. We made the set up a lot better as years went by.

As an example, when I went to work for Chevy in ’61, the 409 would put out 425 horsepower. When we put the Z/28 on the market in 1967, the Z/28 engine – with a racing cam – would put out 425 horsepower at 6,400 rpm. We made that much progress in camshaft design and airflow. That’s a 100 cubic inches less. Obviously the torque wasn’t the same, but the horsepower was the same.

All the NASCAR teams eventually bought an optron during the 90’s. They do their own valvetrain evaluations, durability tests, and everything. They may have something that’s beyond the Optron now, I don’t know what it is because I kinda lost track of it. But that was a magical instrument in those days.” Editor’s Note: The Spintron is now the tool of choice.

CHC: Did you started with General Motors as a test engineer?

Howell: “What they do in the test lab, is they’ll bring in a new engineer and have him running engines, taking them apart, putting them together, swapping parts, and running the tests under the direction of another engineer or somebody with experience. When they get familiar with the product, they are promoted to actual engineer status, and in my case, it took about a year to get promoted. They want test engineers to write up the instructions for the operators as to what to test. You don’t test anything without a written order, because they don’t want people going off on their own inventing, discovering, or blowing things up. A lot of that stuff got blown up, believe me![laughs]”

CHC: After starting as a test engineer, where did you end up in your career?

Howell: “I was a test engineer up until the summer of 1967, and that was exclusively in the laboratory at Chevrolet Engineering. Then, they promoted me to another level, and I went to work for Vince Piggins, father of the Z/28. Vince ran the performance group that they gradually built, once the corporation decided that maybe racing wasn’t all bad and it wasn’t going to cost them all their profits. One of the things that you need to realize is that when all the corporations got out of racing in 1957, most of them quit making their heavy-duty parts. Chevrolet decided they wanted to keep their good parts in the catalog so you could buy them from a dealer.”

“In essence, that’s what made every Saturday night racer a Chevrolet racer – he could buy the parts. In that time period when none of the manufacturers were really participating in anything other than maybe NASCAR, we were building a racing base with the Saturday night racers who were racing Chevrolets. They were towing them back and forth to the race track with a Chevrolet truck too.”

CHC: What are the differences between the Mark I, Mark II, and Mark IV big-blocks?

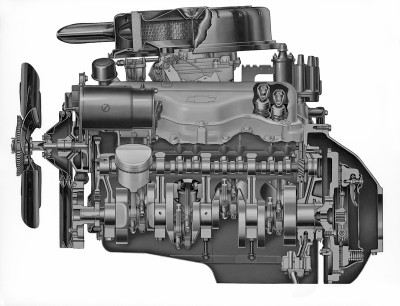

Howell: “The Mark I, the 409, was a design where the block deck was not perpendicular to the bore. The cylinder block was machined on a slant to the bore, and the head was just a flat piece of metal with a couple valves in it. It wasn’t a bad truck engine, but it was a design that engineering staff came up with and it was a flop.

For the Mark II, we had some initial 409-displacement engines running, then we brought that up to 427ci, which was the NASCAR legal limit at the time. The basic difference was, the decks were perpendicular to the bores. The cylinder heads had the valves arranged like the Mark IV, where they came in at two angles instead of just straight in and down into the bore. I’m sure you’re familiar with the difference in the Mark IV head from a small-block. The Mark II’s originally had the same crankshaft, main- and rod-bearing diameters of the 409 engine. Also, you couldn’t swap heads from side-to-side, they were designed with a right and a left orientation. We kept developing that engine right up into 1964, and then we started the development of the Mark IV.

The Mark IV engine retained the different valve angles, but the cylinder head could be swapped from side to side. There is also an increase the main- and rod-journal diameters. They also went to a four-bolt main bearing to combat cap walk.”

CHC: Was the design process more trial and error, or more from an engineering stand point?

Howell: “I hate to say that it was trial and error, but it’s almost all trial and error. You put the best designers you have on a task, and they’ve got the knowledge they have developed over the years, and they draw parts up or have them drawn up on the drawing board to their satisfaction. Then, they build a prototype part and it goes to the test lab along with the engine, or the engine itself goes. You would then have a GM-standard series of tests that are run.

If it met those standards – or even if it didn’t, you fed that information back to the design engineer, and he said ‘okay lets change this or that,’ and do another prototype. That’s pretty much the way engines were done. Honestly, that’s the way they’re still done today. There’s no magic to it. It’s all based on past design experience and development. My career was in development.”

CHC: The Mark II that was developed never made it into production or into any cars?

Howell: “No, it never went into production. In the 1963 racing season, there were probably 15 of them running in NASCAR over that summer. As people wore them out, they couldn’t get replacement parts. Junior Johnson managed the whole year in 1963, and won the championship with a Mark II. But that’s pretty much the end of it until GM got back into NASCAR around 1972.”

CHC: What were the cubic inches of the Mark II engine?

Howell: “It started as a 409, then we swelled it up to 427. In 1963, we heard NASCAR was going to a 396 cubic-inch limit, so we started making it as a 396. The first 396 development engines I had were Mark IIs. We switched over and started doing the prototype Mark IV’s, which were also 396 cubic inches. The first production Mark IV’s in 1965 were all 396 cubic inches.”

CHC: The 396, as we know it, came about because of a NASCAR regulation?

Howell: “Most people wouldn’t realize it, but a NASCAR rumor made us change displacements.[laughs]”

CHC: What changed the policy of Chevy to give the green light to bring the big-block into the mainstream?

Howell: “If you could put an engine into a production car there was no problem with it. Of course, performance cars were starting to take off in the mid ’60s, and we had good performance engines sitting on the shelves, because we had been doing this development. We started sticking them in Chevelles, Corvettes, and whatever else, as soon as we could. The corporation didn’t actually get into what you called professional racing until Trans Am came along and we pitted the Camaro against the Mustang. That was all done with a small-block, though.”

CHC: What was the mentality of Chevrolet back in the 1960’s?

Howell: “The general public, the news media, and even the magazines were not aware of what we were doing behind closed doors at engineering. The Chaparral program and our connections with Jim Hall were completely secret.”

CHC: Did Chevrolet do a lot of things behind closed doors?

Howell: “Experimenting? yes? But, I guess I don’t know how they justified the Chaparral program for instance. They did run it with an automatic transmission, I do know that. That might have been some value. I think maybe they got some aerodynamic benefit from it, and they also developed some technical measuring and transmitting by radio, so you had real-time data coming off the test car that you could analyze immediately. That was new at that time.”

CHC: What was it like to work for GM back then? Was it stressful? Exciting?

Howell: “I would say it was very exciting. It certainly was for me. I think most of the dyno operation stuff was very interesting to the people that were involved in it. The Chaparral stuff was done in what we called R&D, and they were behind locked doors. They did run their stuff on the same dynamometer as we did, so we were a little aware of what they were doing.”

CHC: How quickly did development happen back then?

Howell: “I think at that time, we were probably running two shifts in the machine shop, and some people were running six days a week. Before the advent of computer-aided drafting, it just took time to do stuff.”

CHC: What did you do after you retired?

Howell: “In 1987, I was still too young to sit around and do nothing, but GM had a reduction in the work force, and they were looking to eliminate jobs. They were offering early retirement to people, and that’s what I took. I knew fuel injection was a coming thing. At that time, only the Corvette had port fuel injection – with eight injectors. There were people wanting to put Corvette engines into other cars. So I thought I would learn how to build wiring harnesses and maybe that’ll be a thing. It turned out it was a good idea.[laughs]”

We would like to thank Bill Howell for taking time out of his day and giving us a sneak peak back into the history of Chevrolet. Next time you see a big-block, you will know just a little bit more about them than the person standing next to you.