Question – When is a small-block Chevy not a V8?

Answer – When only half the pistons are pushing up and down.

In this particular case, it’s all in an effort to build an old-school dry lakes / Bonneville class V4 configuration. But it may also be inadvertently starring in its own unique version as it is among the smallest displacement small-block Chevys ever built. When you squeeze the bore down to 3.562 inches and combine it with a 3.00-inch stroke 283 crank, you end up with a tiny dancer displacing a mere 119.6 cubic inches. We added the decimal place for sheer moral support.

They say you can’t judge a book by its cover – or a small-block just by looking at it. The visual hint that something atypical is happening here are the four blocked off inlet horns in the Hilborn mechanical fuel injection manifold.

Willie Freudiger is the man behind this project, but while unusual, it’s not a new concept. This engine is actually based on an earlier version he and his dad built years ago. Plus, his son drove a larger (which is a relative term here) 177ci version to a 200 mph club record in the family Modified Fuel Roadster. Freudiger plans to bolt this smaller effort in the car for the dry lake, mainly, “So I can take on those Pintos,” as he puts it.

This is a decidedly old-school approach to achieving a class record. Willie doesn’t rely on computers or electronics – he prefers to build and race engines in the time-honored tradition of a flat tappet camshaft, mechanical fuel injection, and a special magneto. This smallest bullet will include some new Don Jackson Engineering nozzles, iron smog heads, and small valves, because larger ones won’t fit in that tiny bore. But perhaps the best part is that he intends to make noise using a serious load of nitromethane. “We’ll start right at 82-percent. If it’s happy there we might go up a little for the dirt.” This is old age and treachery at its finest.

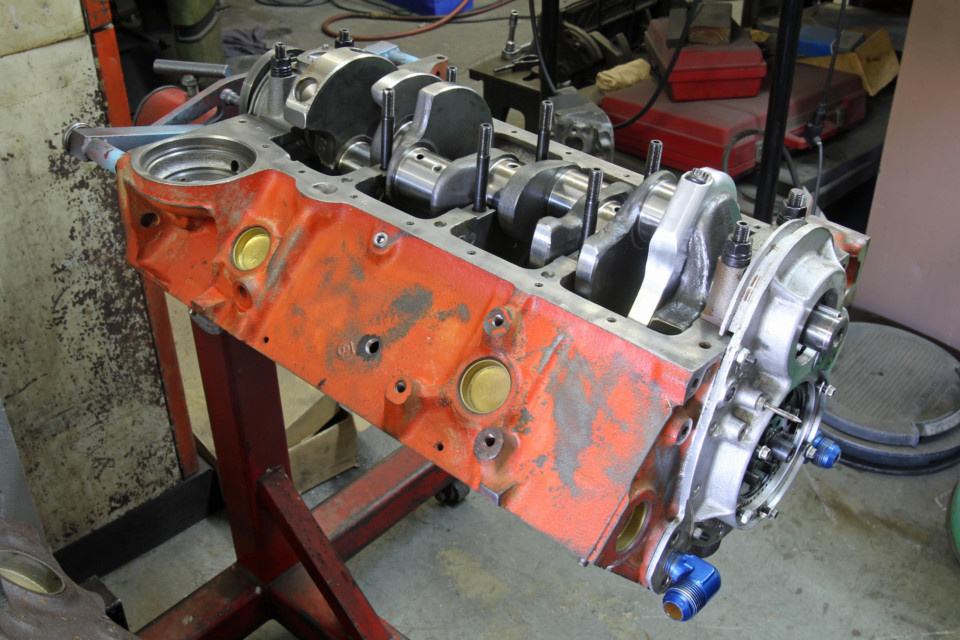

Look closely and you’ll see the two outer bores on the left side are smaller – 3.562 inches – than their standard 327 4.00-inch inboard counterparts. On the opposite side, the operating bores are the two inboard ones. This combination was created out of necessity to stay under the 122ci limit for the class.

Diminutive and Deceptive

We learned about this distinctive little small-block from Don Barrington, Jr. at Barrington Machine in Valencia, California. He performed the cylinder sleeve machining and installation and assembled the little V4. The really interesting part of this is the orientation of the firing order. A small-block Chevy firing order is 1-8-4-3-6-5-7-2. Willie’s four-banger employs the outboard cylinders 1 and 7 on the driver side and the inboard cylinders on the opposite bank with holes 4 and 6. With a firing order of 1-4-6-7, this fires a cylinder every 180 degrees. While that does concentrate the paired firings of cylinders 4 and 6 on the even side of the block, it was necessitated by the stock firing order.

To address the questions that will inevitably flow for this story, most of the decisions made around this engine were driven by the imperative to minimize the cost. The budget constraints necessitated the near-stock iron heads, an early small-journal 327 block, and a stock, forged 283 crank. However, if this engine is successful, Freudiger may indulge in better heads and a roller cam. But for now, this is an experiment to see if they can lay down enough power to exceed the current Bonneville record in G/ Fuel Modified Roadster (G/FMR) held by an under-2.0L overhead cam Pinto engine. Freudiger’s goal is 500 hp.

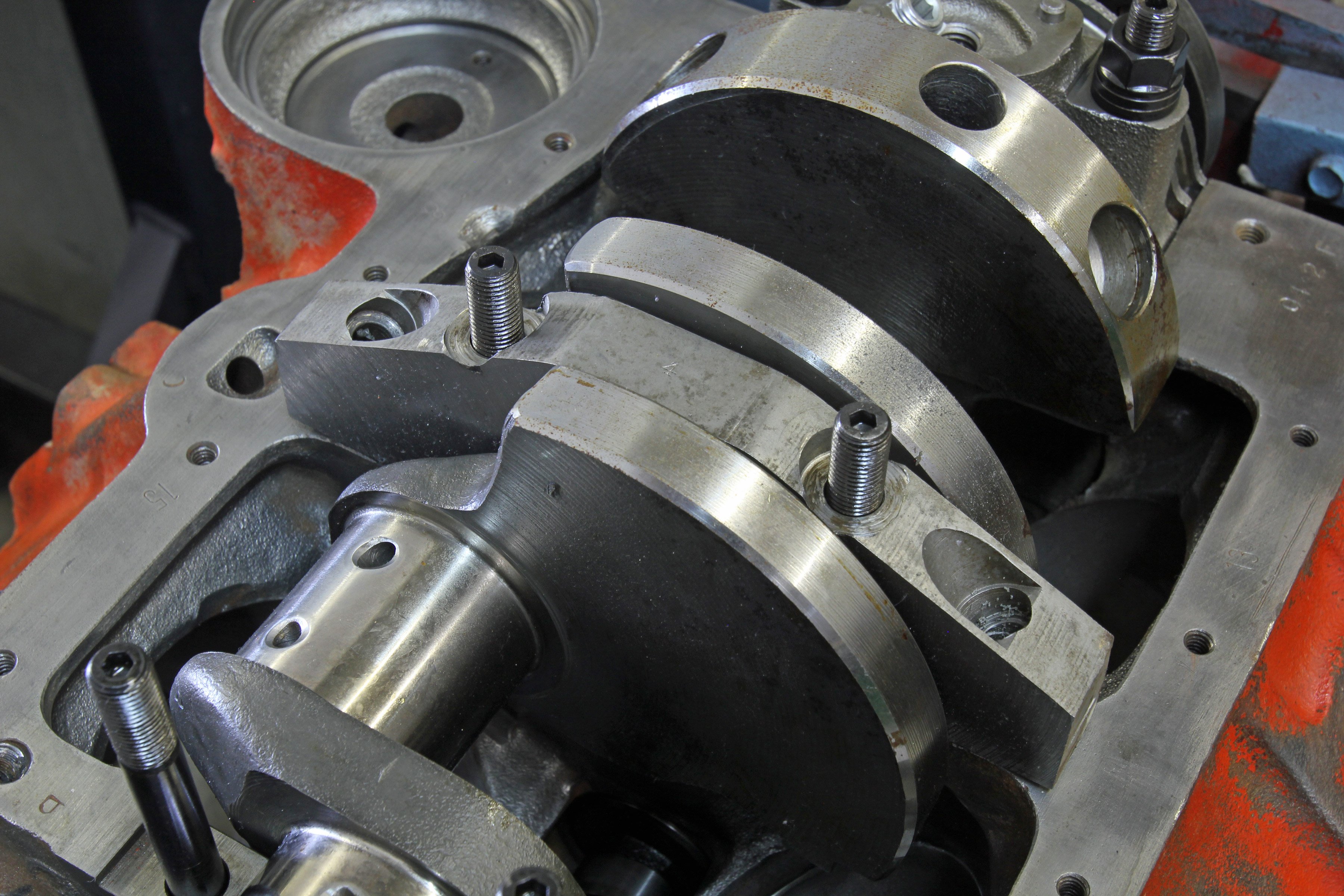

(Left) Call this a rod spacer. There are four of these that take up the space normally occupied by the other four connecting rods and are complete with bearings set with the proper bearing and rod side clearances. (Right) This small journal 327 block is enhanced with steel splayed, four-bolt main caps using ARP studs to ensure the mains stay in place when subjected to those serious nitro loads.

Getting to 2.0 Liters

Achieving his goal filters down to tweaking the bore and stroke. Conventional wisdom contends that a big bore and short stroke are the keys to making power. While that’s true, it can also get expensive. In order to enjoy the benefits of a large 4.00-inch bore, the stroke to remain under the 2.0-liter (122 cubic-inch) limit on a four cylinder would be limited to only 2.42 inches – creating 121.6ci. That would require a custom billet steel crank, since even the shortest raw forging could not be cut down to that short of a stroke. The cost of a billet crank for this project was absolutely out of the question.

Of course, to make power with a little engine like this means you have to spin it to much higher engine speeds than you’d expect to see out of the base small-block Chevy. Freudiger says his goal is 7,000 rpm, and with the short stroke and lightweight rotating components, that shouldn’t be a problem. If anything, it’s the valvetrain that might be the source of difficulties, but with today’s off-the-shelf valvetrain parts, 7,000 rpm isn’t a serious challenge.

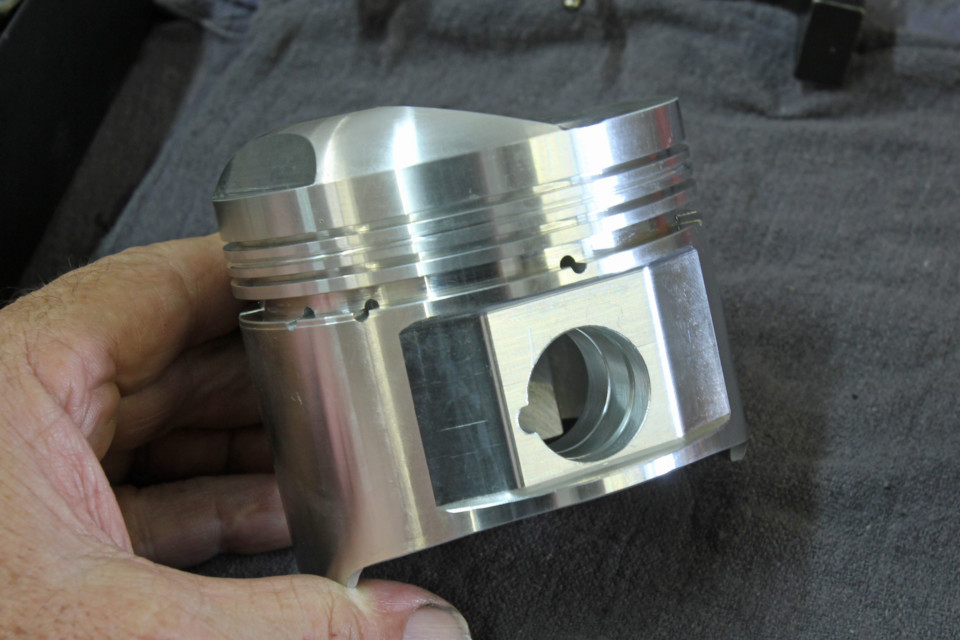

Willie chose a set of Arias pistons with a big dome that is necessary to create as much compression as possible given the short stroke. Barrington told us he had to cut a slot in the dome to create clearance for the spark plug. The rods are 5.7-inch GRP aluminum.

With the fixed 3.00-inch stroke defining the bore size, the bore diameter came to 3.562 inches. To accomplish that, Freudiger contacted Arias Pistons, who built a set of pistons to work with a set of GRP aluminum 5.70-inch rods and the 3.00-inch stroke. Since the goal from the beginning was running on nitro – compression wasn’t a huge concern because the static numbers would be relatively low anyway. Once all the variables played out, compression ended up at 7:1, although Freudiger would have preferred to have more. “The problem is those crappy heads,” Freudiger says. “The chamber is just too big.”

This is still an experiment of sorts. To keep it manageable, he also went with a flat tappet camshaft from Engle. It specs at 270 degrees intake and 284 degrees of exhaust duration at 0.050-inch, with 0.557-inch intake lift, and 0.0567-inch exhaust, with a 108-degree lobe separation angle.

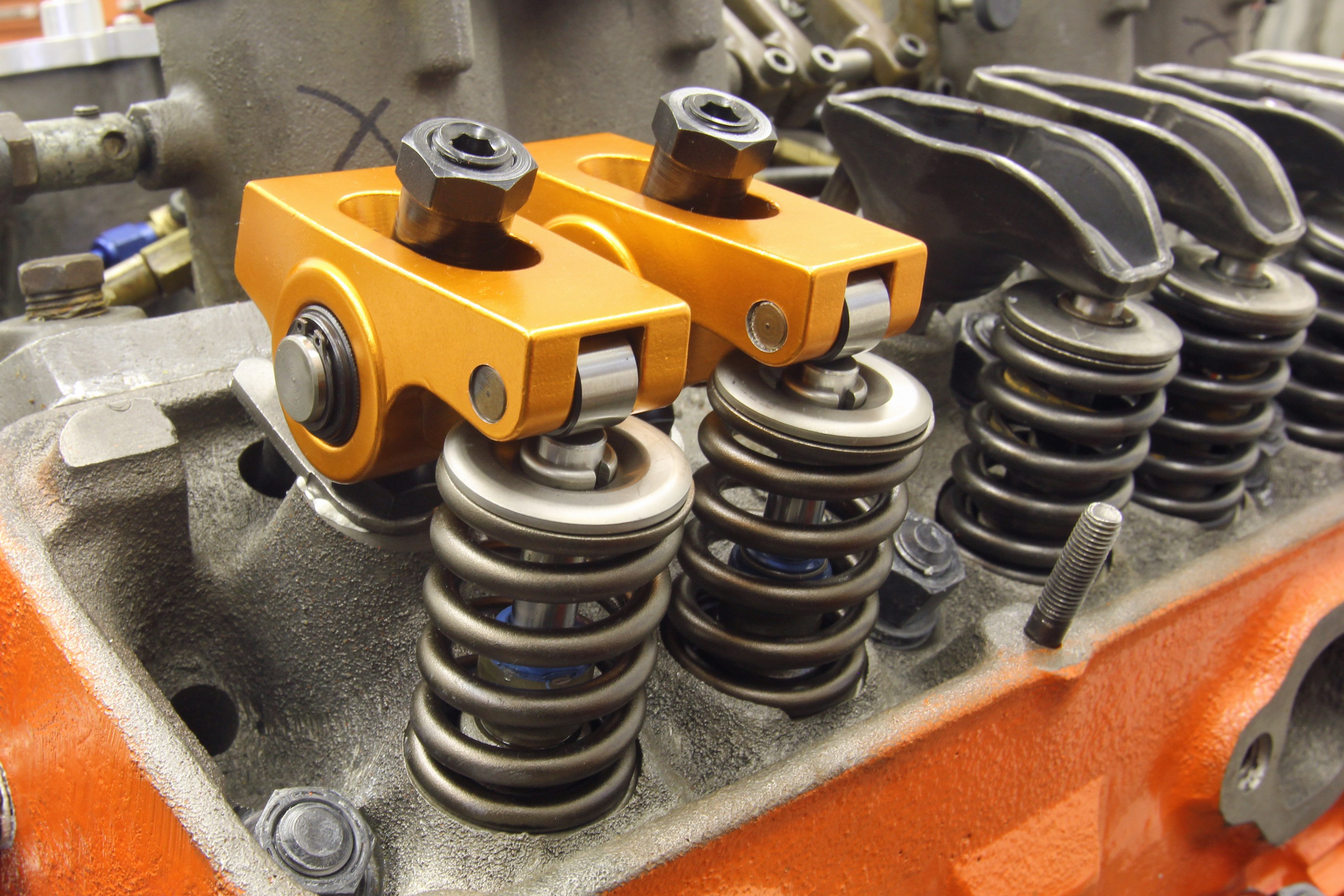

The valvetrain is also relatively simple with just a set of Manley valvesprings with 130 pounds on the seat and 330 pounds open load, working with a vintage set of titanium retainers to minimize the inertial forces. The springs are still only 1.250-inch diameter because Barrington noted these heads don’t allow opening up the spring pocket. Doing so on these heads results in hitting the water jacket. The rockers are a set of Harland Sharp 1.6:1 rockers and there’s no current plan to add a stud girdle.

(Left) The stock iron heads are straight off of a Goodwrench crate engine and feature 1.95/1.50-inch valves. A light amount of porting was done on the exhaust side in hopes of improving the power. (Right) No expensive shaft rockers here. Instead, a simple set of Harland Sharp 1.6:1 roller rockers, a set of Manley valve springs, titanium retainers, screw-in studs, and a hope for the best. The stock rockers and springs on the valves are there just to seal up the engine.

Fire In The Hole

Short of the Arias pistons and GRP aluminum rods, the Hilborn mechanical fuel injection might be the most exotic, race-inspired part on the entire engine. Externally, the dead giveaway to this V4’s true identity are the manifold block-off plates covering the unused intake runners. Just like a standard SBC, the mechanical fuel pump bolts to the front of the cam cover and will supply the required load of nitromethane.

Ignition for this unique setup has been a challenge for Freudiger in the past. In the previous engine, he used an eight-cylinder magneto that fired four plugs bolted to the firewall. For this effort, Freudiger came up with a four-cylinder motorcycle magneto from a 350cc Honda that has been adapted to the lower portion of small-block Chevy distributor. Tom Cirello of Cirello Magnetos modified this package with better magnets and this promises to help keep the candles lit at full boogie.

(Left) This is a lifter plug, if you will. A small-block Chevy pushes all its oil through the lifter galley first, so Vinny had these plugs machined with an annulus (groove) through the center to direct oil to the mains and the rest of the engine. (Center) The pushrods and lifer plugs are in place here. While a typical small-block camshaft is used and maintains its 16 lobes, half are not in use and these plugs do not contact the lobes so they don’t create lift. The pushrods are in place to ensure the lifter plugs do not escape. (Right) The pushrods and rockers are in place for the non-operating cylinders to ensure the lifter plugs do not escape which would immediately kill oil pressure. Also note this is an old school 327 block complete with its road draft tube opening at the rear of the lifter valley.

The tune up on any race engine is critical and this little V4 will be no different. Freudiger has years of experience in this area. Part of the advantage to this V4’s low static compression ratio is that with nitromethane, plenty of ignition timing is part of the plan. Most nitro engines run 50 degrees of total timing and sometimes, even more than that. Part of this, according to Top Fuel guru Bill Miller, is because the best-power air-fuel ratio for nitromethane is 1:1.

This means that the more nitro you can stuff into the cylinder, the more power you can make. According to Miller, as much as 90-percent of nitromethane in the cylinder at wide-open-throttle (WOT) is still a liquid, so to initiate enough heat early in the combustion cycle to vaporize the fuel so it will burn, 50-plus degrees of ignition timing are necessary.

Look closely and you can see where an 1/8-inch pipe hole has been drilled and tapped into the water jacket. This is the new coolant drain location because Barrington filled the lower half of the block with block filler to add strength.

“But,” Freudiger says, “you’ve got to make it live too. For the dry lakes we might run more timing — we’ve run 58 degrees of timing at El Mirage — but you can’t run that much at Bonneville. Remember, you have to make it run twice to get the record. You don’t want to detonate it.” So the Top Fuel strategy of making the engine live one foot past the finish line doesn’t apply here.

So welcome to the world of one-off Bonneville engines. Freudiger’s effort may seem bizarre and to some, perhaps even crude. But this represents a glimpse into the creative world of salt flat and dry lakes racing where often it is the innovators who set themselves apart from the thundering herd, and earn their place in the record books.

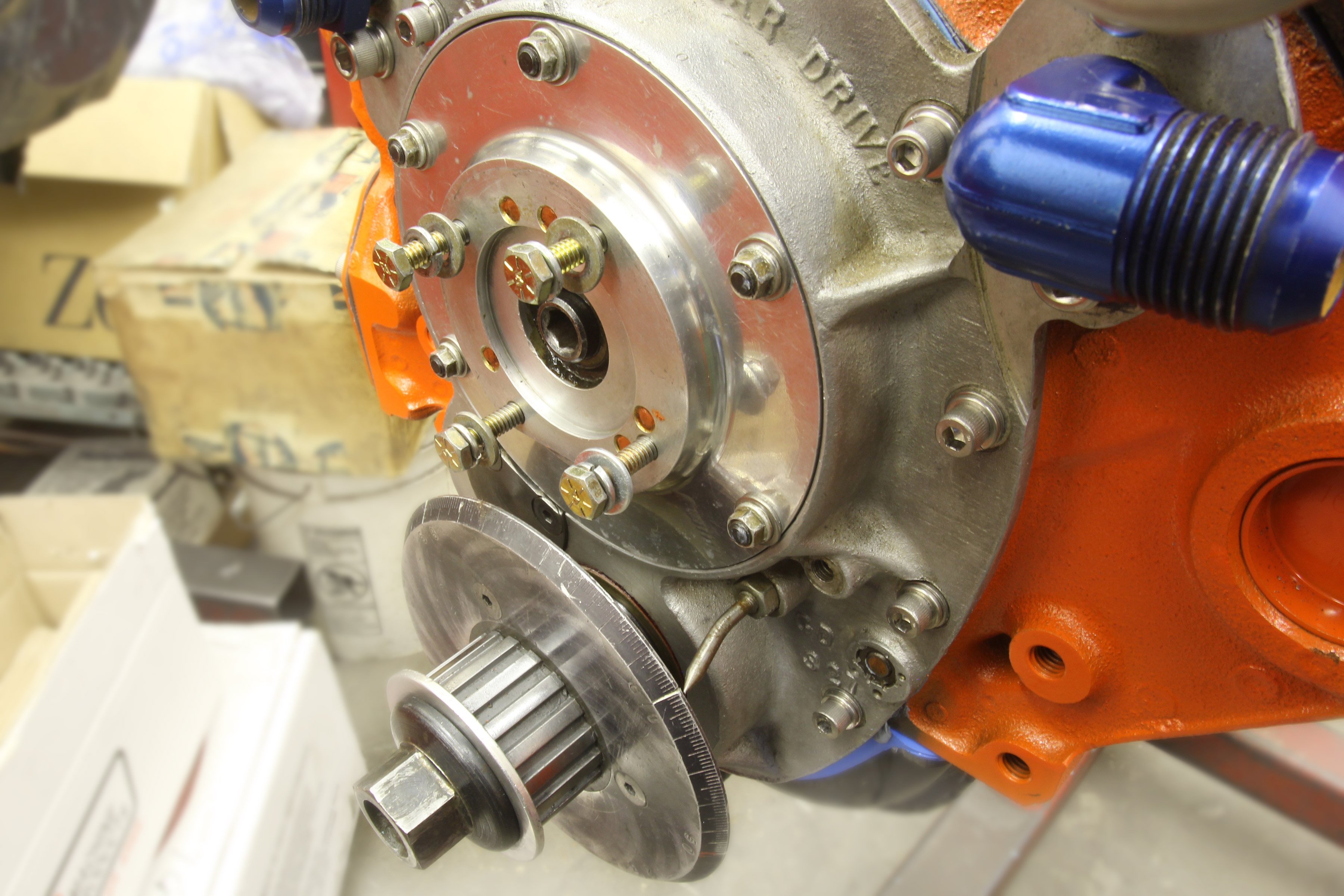

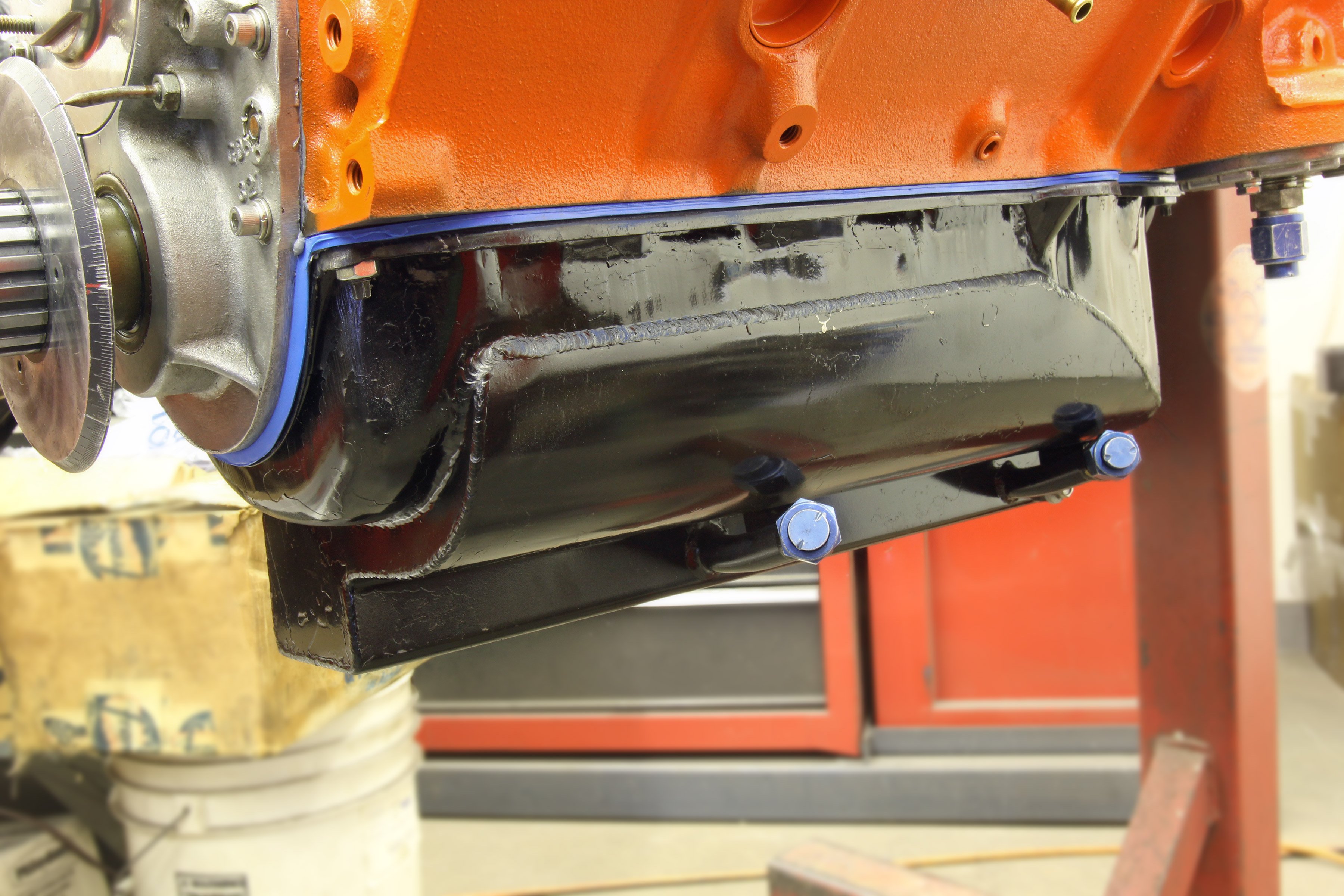

(Left) No need for a giant harmonic balancer. The aluminum cover includes a drive to spin the mechanical fuel pump directly off the camshaft. According to sources who know such things, this setup has a rather positive damping effect on valvetrain harmonics. (Right) Freudiger did add a dry sump system to this engine that uses a pair of scavenge points in the pan to minimize windage and also pull some crankcase vacuum.