A decade ago, Chris Alston Sr., a guru of chassis and chassis components for everything from drag racing to Pro Touring muscle cars, penned a number of informative tech articles that ran in the annual catalog of the company that bears his name, Chris Alston’s Chassisworks, that focused on topics and questions that targeted would-be racers and enthusiasts interested in learning more about chassis and what it’d take to get their project up and running. But as the company’s product selection exploded year by year, so too did the size of its catalogs, and over time these articles were phased out of the print catalog placed in the hands of untold numbers of gearheads the world over. But now, thanks to the Chassisworks team, we’re bringing these valuable stories back to life with current information that brings them up to speed with today’s chassis standards and offerings.

This first installment delivers tips for frame and chassis selections and dives into a number of relative topics, from comparing and contrasting subframes to chassis, box and round-tube rails, materials, A-Arms and struts, and much more.

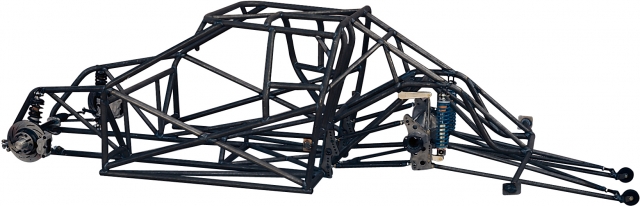

An important first step is determining whether you need a full chassis or a subframe, and much of this rests of what your plans are for the car performance-wise now and in the future, and what you have to spend. Shown where is a complete door slammer chassis with a Funny Car cage with suspension components installed.

Subframe vs. Chassis

First, you must decide whether you need a “back-half” modification or a full chassis. The advantage to the back-half conversion is its price: about $3400 for a complete Chassisworks subframe, FAB9 housing, ladder-bar or 4-link suspension, coil springs and mounting kit, shock absorbers, roll cage, wheel tubs, and everything else you need.

To get a back-half car to go fairly fast — say, low 10s — is not that difficult, but weight distribution becomes a problem. Because the rear is so much lighter than the front, it’s hard to make the car perform consistently and react quickly. If you plan to go quicker than 10.50, you should definitely consider a full-chassis car.

Chassisworks offers a range of back half options for cars in the 10.50 and slower ET range, in ladder bar (shown with box-tube rails at left) and Avenger or Eliminator four-link-style setups, seen here as complete rear suspension packages. If you choose to go this route initially rather than building a full chassis, you can later add a front clip to create what is essentially a full Eliminator-style chassis.

If you purchase a Chassisworks subframe, you have another option: You can start out with our rear-subframe kit now, and install one of our A-arm or strut front frames later — turning your back-half car into a full, Eliminator-style chassis. In fact, our front-frame kits are specifically designed to be added-on later, without making the finished chassis look like it was built in two parts.

Box vs. Round Rails

Some Eliminator series chassis are available with box-tube main frames. While these are commonly thought to be stronger and easier to construct, Chassisworks contends

Anyone who decides to step into a full chassis must next choose between a box frame or a round frame. Fact: There is no advantage to a box-rail car! A lot of people are under the mistaken impression that a box-rail car is stronger; in fact, the strength of any car comes mostly from its roll cage. While a box-rail frame is physically larger, it’s also made out of thinner material. And it adds about 30 pounds to the car — a considerable amount of weight, considering that a round-tube chassis costs about $100 less.

Once upon a time, a box-rail car was somewhat easier to assemble, but that’s not the case anymore. Because of the way we build our Eliminator-series cars — and because Chassisworks instructions are so detailed — the round-tube version isn’t any harder to build.

Now, if you’re still uncomfortable with building a round-rail car, that’s a real good reason not to buy one! But from a strict performance standpoint, it’s better in all applications, because it’s lighter. Another slight advantage is that a round-rail car sits lower to the ground because its frame isn’t as tall.

Roll Cages

With the advent of ultrasonic testing in sportsman categories, there’s a lot of confusion about mild-steel roll cages. We use .134-inch-wall tube to assure that your chassis will pass NHRA’s (.118-inch) minimum wall-thickness requirements.

The completed 10-point roll cage in one of of our previous project vehicles, the MaxStreet ’66 Chevy II.

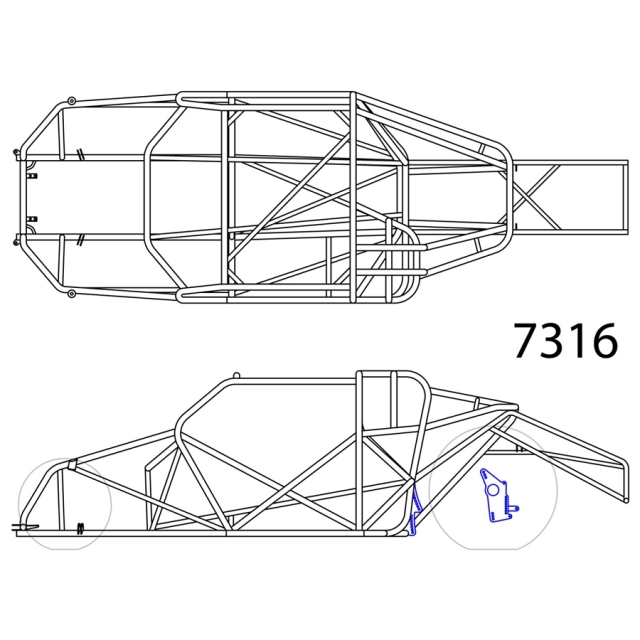

Next question: Do you need a Funny Car cage? Our standard Eliminator chassis is plenty safe without one, but there is a performance advantage. If you want to run better than 8.90s, you should consider one because it makes the car stiffer and, consequently, more consistent. Plus, if you want to feel as safe as possible, it does afford more protection. But you’re going to pick up about 30 pounds, and spend about $165 extra. (If you buy a standard Eliminator chassis now, you can always add our Funny Car kit later.)

Elapsed time -- and the power needed to accomplish it -- are the determining factors in roll cage selection. A Funny Car-style cage is not only safer, but provides far more stiffness to the roll cage area and therefore the chassis as a whole. A roll cage, like the 8-point shown at left (with optional bars highlighted in blue) are an excellent choice for lower-horsepower race cars.

Mild Steel vs. 4130

Some people believe that 4130 chrome-moly cars are stronger than mild-steel cars. Not necessarily! While 4130 tubing is a stronger material, because it’s made out of an alloy steel, the rules let us use thinner material (.083- and .065-inch wall). Thus, a stronger material that has a thinner wall is about as strong as a thicker-wall mild steel. The 4130 chassis is going to be 20- to 25-percent lighter because it’s made out of thinner material; there’s simply less steel in the car. Basically, what you’re paying for when you buy a 4130 car is weight reduction. In a basic Eliminator kit, you pay about $900 extra to save 70 to 80 pounds.

Pound for pound, chromoly is a stronger material than mild steel, and that allows for chromoly to be a thinner wall tubing (.083″ compared to .113″). This gives chromoly a distinct advantage in terms of weight, but that advantage comes at a cost that customers must consider.

Now, some guys would pay a fortune for 70 to 80 pounds. You have to ask yourself: “Could I spend $900 somewhere else, and be better off?” If you have cast-iron cylinder heads on your engine, and you want a 4130 chassis, you’d be better off buying aluminum heads. If you’re going to go fast — mid-eights or quicker — you probably should get 4130, because mild steel definitely detracts from the resale value of a car like that.

The only real disadvantage is that a 4130 car must be TIG-welded. That means every single accessory, bracket and tab has to be TIG-welded. For the first-time, build-it-yourself type of guy, this is not the way to go; he shouldn’t even consider it. Chromemoly is for a higher-skilled, more capable fabricator. Mild steel, on the other hand, is extremely forgiving.

I also hear people say that 4130 is more likely to crack. Wrong again! This tubing was originally developed for the aircraft industry to make airframe parts, and nothing is stressed worse than airframe parts. If this stuff didn’t have excellent fatigue life, it wouldn’t be in airplanes. I have never seen a worn-out 4130 “door” car that was assembled correctly. Nor have I seen a worn-out mild-steel car that was assembled correctly. So, durability isn’t really a consideration.

A-Arms vs. Struts

In the front end, you’ve got two choices: A-arms or struts. If money’s tight, an A-arm car is cheaper to build. If you have the money, you can consider building a strut car. The disadvantage to struts is that they cost a little more money. The advantages are lighter weight and better header clearance. In a narrow car like a Monza or Vega, or most big-block cars, header clearance can be a real problem. In a wider car, like a Camaro, it’s not as big a factor because the frame is wider, so the A-arms are farther apart. (Our exclusive A-arm design goes a long way towards solving this problem by exposing the exhaust ports more than other A-arms.)

Chassisworks’ front subframes (shown here with A-Arma and rack-and-pinion steering) can remove as much as 300 lbs. from the nose of a vehicle.

As for performance, the reality is that the strut is not an infinitely better suspension than the A-arm. In some cases, an A-arm might actually work better, because it has a bit more front-end travel than a strut. If you have a nose-heavy car (which most cars built economically tend to be), or a high-horsepower car with a marginal tire, more front-end travel is an advantage.

The modified MacPherson strut is the latest technology. For anybody who’s building a serious car, it’s the preferred choice. An internally adjustable strut must be taken off the car for adjustment of its valving; an externally adjustable strut can be readjusted without removing it from the car. The latter is a very sophisticated piece. In the hands of a person who wants to spend some energy working on it, that’s an advantage — not because of the strut, but because the shock absorber is adjusted externally, and has more control and more variables. A well-equipped strut car is going to be a few hundredths faster than a well-equipped A-arm car.

If you have the money, you need to decide. Even with the spindles and shocks that must be purchased along with A-arms, the cost is still several hundred dollars less than for struts. The weight difference is typically between 15 and 20 pounds, depending on the style of frame you’re using. That’s a lot of weight in a 7.90 car, but 20 pounds isn’t worth a dime in a Super Gasser.

Double Frame Rails

Double framerails, like shown in this drawing of a ’55-57 Chevy Avenger Pro Mod chassis, is a hallmark of high-horsepower door slammer, proving structural support and rigidity to handle the power that supercharged, turbocharged, and nitrous engines put to the ground.

If a customer wants to run quicker than 7.90, we insist that he step up to our double-frame-rail, Avenger-series car. The reason is not that our Eliminator chassis won’t go that fast; it’s just that the kind of horsepower it takes to run that fast will flex a single-rail car excessively. You need the double rails to deal with the extra horsepower. A flexible car takes more power to go the same speed. When you want to run low sevens or high sixes, it takes every bit of horsepower you can find, muster, beg, borrow and steal; you can’t let the chassis use any of it up.

Some people believe that a 7.90 car can be upgraded to a 6.90 car, but they’re designed and built completely different. A nitrous or blower motor makes so much torque, and flexes the car so much more, that you need extra tubing and a considerably different design to support this brutal horsepower, so the car will stay flat and track correctly. If you plan to go faster than 7.90, you need the double frame rails and other advantages built into our state-of-the-art Avenger chassis.

In a lower-horsepower car, double rails can be too stiff. A notable exception is our Nostalgia chassis for older, fat-fendered cars. Because these bodies are so narrow, we can’t put the roll-cage supports in the same places that we do in our late-model cars. The double rail frame is another way to stiffen the chassis. Plus, these older bodies are so tall that we have extra room to make the frame taller, and still fit it under the stock floor.

As a general rule, if you want to run 10.50s or slower, install a back-half suspension system. If you want to run low tens to high sevens, build an Eliminator I or II chassis. If you want to go quicker than that, buy the Avenger chassis.